Was Paul a Roman Citizen?

Introduction

Historically this is an interesting question because it helps to establish both the historicity and accuracy of the biblical text.

That is, that in making the claim it helps to center the text into a specific time frame where, should the character in question be in a place or period where the statement would be meaningless or uncalled for it sets the statement up as suspect.

Many of the accusations against the authority and accuracy of the text of Scripture has been allegations of falsehood (things are just made up) or that it engages in instances of anachronism (getting things out of their place in time).

However, as we have learned more about the text—as a historical phenomenon—and about ancient texts in general, we have discovered that where there are anachronisms (say with place names), there is usually—either in the same text or another—that the name was changed at some point for some reason.

Furthermore, we have learned that ancient scribes would often update texts with new words, or alternative spellings, or even inside jokes. Those actions display that the such practices were completely acceptable to the original audiences. Once we understand these facts the accusations disappear, though the ghosts remain, repeated ad nauseam on the interwebs by unbelievers.

But what about the Apostle Paul?

On a recent episode of his podcast Bible Study for Amateurs, Ben—the Amateur Exegete—dives into the question of Paul’s citizenship.

But First…Some Context

The question of Paul’s citizenship arises from the instances where it is appealed to by the Apostle.

The first such appeal by Paul is found in Acts 16, when Paul and his companion Silas are arrested in Philippi after casting a demon out of a slave. After being arrested, beaten, and thrown in jail overnight—not to mention being subject to an earthquake while imprisoned—when they are summarily released, Paul and Silas both invoke their citizenship as Romans as a protest for their mistreatment by the city officials.

The Second instance is in Acts 22 when, following events that began in the previous chapter, Paul is—again—about to be flogged by the cohort, he again invokes his Roman citizenship. Subsequent to this, Paul is put in prison by the Roman governor and kept there, until Paul appeals to Caesar and is dispatched to Rome.

Roman citizenship provided people with certain advantages such as the avoidance of degrading punishments (eg flogging) as well as exemption from local jurisdictions in certain cases, not to mention the right of appeal to the emperor.[1]

Now, the issue for critics is that Paul doesn’t spend a great deal of time discussing his Roman citizenship, in fact—outside of Acts—the subject is never mentioned. This relative silence, Ben insists, doesn’t mean that we should simply accept what Luke says about Paul’s citizenship (3:50ff).

To support this skepticism, Ben appeals to Pauline scholar Calvin Roetzel and his book Paul: The Man and the Myth (T&T Clark, 1999), wherein Roetzel gives his readers four reasons to doubt Paul’s citizenship [2]:

- In the eastern edges of the empire it was rare to grant citizenship to Jews unless they were wealthy or influential.

- If we see Paul’s personal piety as reflective of his familial piety then it was unlikely that Paul was a citizen.

- Epistolary silence argues against it.

- It serves Luke’s theological ends.

Now, to each of these reasons there is a logical response. For point 1, rarity doesn’t mean that it didn’t happen. For point 2, if Paul’s citizenship was inherited there’s no reason to assume that his personal piety is reflective of his parents. Point 3, is an argument from silence and we should recognize that these are inherently fallacious. And point 4 is a big, SO WHAT?

Roetzel does argue that Jews generally had a type of citizenship that was related to their ethnic position in society that gave them “the right to create their own administrative and judicial organization”.[3] This gave the Jews something of “an intermediate status between citizens and resident aliens”.[4] However, if Paul was a Roman citizen, and not just someone of intermediate status—Roetzel admits—it would indicate that he was from the upper class.[5]

Now, Roetzel (and Ben) insists that Roman citizenship would be unlikely for Paul or his parents due to the fact that it would require them to participate in the civic cult.[6] However, also being Jewish and receiving imperial dispensation and that such activities were limited to public administrators as well as the fact that it was limited to the capital and certain later limited periods counts against such assumptions.[7]

Moreover, we know from Roman citizens who were Jewish and rough contemporaries of Paul that there were no such compulsions and it was usually apostate Jews who set about to more fully participate in Roman society participated in the civil religion in order to better situate themselves socially.[8]

Those Damned Inconsistencies

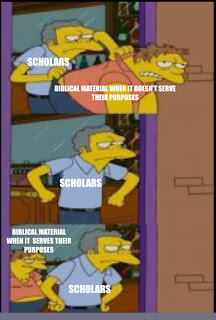

Probably, the most telling aspect of those who wish to skeptically engage with the text and question the veracity of Luke’s claim of Paul’s Roman citizenship often do so to their own detriment due to inconsistency.

Some of Ben’s closing remarks on this point are most instructive, when he says at 6:50,

…[If] we’re looking at these texts through a historical-critical lens, we can’t just take Luke’s word for it.

To that point, I would direct the reader and the listener to Roetzel’s points three and four, because they provide the basis for a refutation of any argument against Luke’s trustworthiness.

For example, Paul’s silence in his epistles would not only extend to his citizenship but also his origins. This is due to the fact that no where in the epistles do we find any reference to his being from Tarsus specifically, or the region of Cilicia in general. These connections are only found in Acts. As Martin Hengel has noted,

It is remarkable that despite the present widespread tendency to question almost everything that Luke says, this information that Paul came from Tarsus is, as far as I can see, barely doubted.[9]

As skeptical as Roetzel is of Paul’s Roman citizenship, and as much as he wants to dismiss Hengel’s opinion, he is entirely dependent upon Paul being from the Jewish Diaspora by appealing to “Paul’s hellenization in a Jewish community involved with and influenced by the dominant Hellenistic culture” that is “evidence of Paul’s deep roots on Jewish tradition engaged in a conversation with the Hellenistic milieu” by the apostle’s “rich Hellenistic vocabulary” and the use of “Stoic diatribe and Hellenistic rhetoric”.[10] To that point, Roetzel notes,

…Paul’s knowledge of and response to the tension between insiders and outsiders, between his own native religion and popular religions of the day, are best understood within a context such as Tarsus offered.[11]

Even those who would question Paul’s origins from Tarsus[12] place him firmly in the experience of the Diaspora.

However, as Hengel notes, such radical skepticism betrays an utter dependence on Lukan material for certain data points.[13] He further notes,

Paul himself is certainly the main source, but we can add Luke as long as there are no really serious objections to him; the bias of which he is constantly accused, a tendency consciously to falsify the true historical situation and thus to invent new 'facts', has proved questionable.[14]

In other words, those who wish to dismiss Luke out of hand where he gives data that Paul omits cannot then call Luke back when he intersects with Paul. Skeptics, in this push-and-pull of Lukan data, want to have their cake and eat it too by denying Luke’s report in one situation as untrustworthy, then sneaking him back in the back door as trustworthy to shore up other historical claims.

Was Paul a Roman Citizen?

There is no doubt that to answer this question one way or another will undoubtedly get one painted with a biased brush.

My chief issue, from a historical-critical perspective, is what do our sources say?

And by sources, I mean those direct, primary sources from which we derive our conclusions. Our only source of information for Paul’s citizenship is the Book of Acts. It claims that Paul was a Roman citizen, but does so in the context of Paul exercising his rights as a citizen, in the face of unjust treatment.

Those who wish to deny the veracity of such a claim have to do so, not on the basis of appeals to silence or rarity or even any alleged bias on the part of the reporter, but on the facts. And if you’re going to dismiss the witness at one place while trying to smuggle him in the back door for support in another, do not expect me to take your rejection seriously.

Selective skepticism is the worst kind of skepticism.

Notes

- Everett Ferguson. Backgrounds of Early Christianity, Second Edition. William B. Eerdmans Publishing. 1993. p. 60

- Calvin Roetzel. Paul: The Man and the Myth. T & T Clark Publishing. 1999. p. 20-1

- Ibid, p. 21

- Ibid, p. 22

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p. 20

- Martin Hengel. The Pre-Christian Paul. SCM Press. 1991. p. 12

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p. 1

- Roetzel, p. 16

- Ibid, p. 19

- Helmut Koester expresses such doubts in his History and Literature of Early Christianity, Volume 2, second edition (Walter de Gruyter, 2000) p. 106-7

- Hengel, p. 20

- Ibid.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment